MENTAL-cont.

The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy

by Judith L. Pearson (2005, 2008)

Hell got much hotter. On a grander stage, France surrendered, Field Marshall Pétain (WW1) became President and Vichy France came into being. But at that point the ambulance corps was disbanded. Virginia followed Claire to the family home near Toulouse.

The consequences of Nazi rule, like tanks but in the form of such things as the racial policies, began to roll in. Virginia was disgusted. She decided that the place to go to find a way to fight was Britain. On the train to Paris, from which she was going to travel to the border with Spain and from Spain make her way to London, she met a man named Bellows with a British accent headed in the same direction. They both detested the Nazis. He said he lived in Spain. Once over the border, he invited her to join him and some friends for dinner. He ended up giving her names and addresses of people in London she should contact about finding a way to fight.

When Virginia went to the American embassy, she caused a sensation because she had actual news of the situation in France. She also got hired. Two weeks after she arrived, however, The Blitz began, September 7. Virginia spent much time in the basement of Mrs. Tipton’s Boarding House over the next 57 days.

One of the contacts Bellows provided was Vera Atkins, who, unknown to Virginia, was a Romanian Jew and assistant to the head of the French section of Britain’s Special Operations

Executive, Colonel Maurice Buckmaster. Vera’s principal job was recruitment/deployment of agents in occupied France. Virginia’s first contacts with Vera were entirely social, tho Vera was very interested in Virginia’s experiences in France. Ultimately, Virginia was invited to meet Vera at a hotel, where the porter took her in a lift to the third floor and Vera’s office. The meeting went well, and Virginia heard the words, “Would you be willing to go back to France working undercover for the British government?”

Weeks of training followed. Morse code. Knife-fighting. Demolitions. Weapons, especially the “Browning repeater,” a light pistol she’d take to France. How to “dead drop” a message. There was one other woman, who became Delphine. Virginia became Germaine. Both passed the preliminary phase and were sent to Scotland. Submachine-guns. Railway demolitions. Plastic explosives. Then to an estate near the English Channel. How to hide a secret. Cover stories (US newspaper reporter, and in fact she got a newspaper to pay her for stories). How to act if caught.

June 22, 1941 -- Hitler invades Russia. Virginia had already been waiting several weeks to get back into France, and by the end of July she was at wit’s end. But in August she was sent to Lyon, with instructions to set up a network, coordinate other agents coming in, and work with the Resistance. She carried counterfeit money, lots of it, carefully worn and soiled to look like the real thing. Her contact was Dr. Jean Rousset, who turned out to be “a gem of a man” and who introduced her to others willing to help, one of whom was already hiding a downed British pilot. Another was the proprietress of a brothel, a very useful woman.

Protecting downed airmen and getting them over the border to Spain became a major activity. Also gathering and distributing supplies parachuted in. Virginia came up with the idea of Dr. Rousset establishing a pseudo mental clinic, where airmen who did not speak French or natives whose activities aroused suspicion could be housed, and dismissed by the authorities. Rousset agreed immediately, and Virginia had the cash.

December 7 meant that “any immunity Virginia had had from the Gestapo evaporated.” Nonetheless, she completed a task she’d been working at for some time. One of the men

dropped in early on had been captured with a note which was the address of a Resistance safe house, all in which were then arrested and sent to a particularly inhumane prison. Virginia

had tried several things, including successfully lobbying the American ambassador to Vichy to get the men transferred to a different prison. Now, it was a matter of a forged

key, bribes for guards, and an escape plan, all of which came to pass. The radio operator she needed was dropped in, but managed to get himself arrested.

Then came a new courier from Paris, one whom Virginia immediately had doubts about, but whom everyone told her was a genuine patriot. He ended up betraying not only Virginia, but her entire circuit in Lyon. And at the same time Klaus Barbie arrived, perhaps the most sadistic Nazi of all and famous for it.

In November 1942 she was told that invasion of North Africa was imminent, increasing chances of her arrest. Moreover, SOE agents were required to return to London periodically.

Virginia immediately took the train to Perpignan in SW France, a staging point for border crossings across the Pyrenees and into Spain. A sympathizer, a businessman, met her there and

arranged for a guide to take her and three members of the Resistance over the snow-covered mountains. A thirty-mile hike, starting at midnight, porting a heavy rucksack. The only relief

was a hidden cabin with hanging cots and a crude fireplace and some wood. They got four hours of sleep. Another upwards to above 7,000 feet, then down to a village, still in France,

where the guide brought them into the house of a young couple with a baby. Cuthbert (the name she’d given to her wood) was causing her problems, but there were straw mats on the floor,

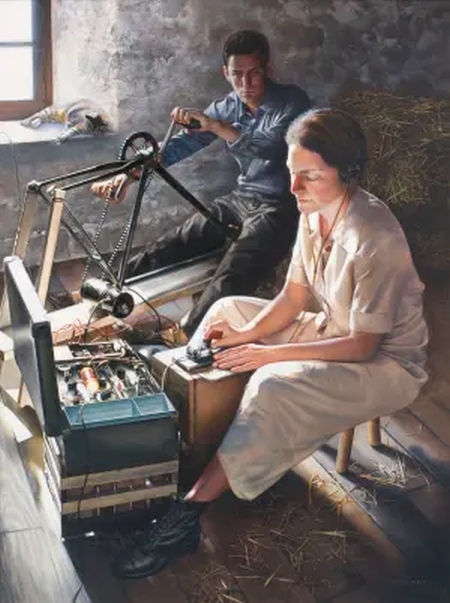

and they all fell immediately to sleep. After a breakfast of coffee and bread, the young man pulled a radio transmitter out of a hiding place. Virginia had departed so quickly, she’d not

informed London, but now was able to do so. They avoided Spanish ski patrols and made it to San Juan de las Abadesas, and safe houses. They were to meet in the morning for the

5:45AM train to Barcelona, too early for any police patrol.

They all arrived at 4:30AM and sat apart from each other. “Just minutes after they had sat down, four Spanish civil guards appeared and rounded them up into a group at gunpoint.”

They were taken to jail cells.

This takes us just to the beginning of 1943, and there is much more, for the world, and for Virginia, but at this point that story is best appreciated by reading Judith Pearson’ s marvelous book.

Some highlights, tho.

-- SOE leaders declined to send her back, too compromised, too at risk.

-- She took a wireless course and got a job with the US’s newly formed OSS, returning to France March 1944, fourth agent sent there, where the job was to empower Resistance groups to support D-Day with sabotage and more. She was disguised as an old peasant, gray hair, teeth filed down, shuffling along.

-- She was wireless operator for Henri Lassot, 62 years old, fifth OSS agent, leader of the new Saint network. She quickly separates herself from him -- too talkative and a security risk.

-- Roaming around southern France, she found and organized drop zones, renewed contacts with the Resistance. Her aim now was to support the Allied mid-August invasion of the south, Operation Dragoon. Despite quitting her disguise, she had trouble getting Resistance groups to accept her authority, though her ability to bring in needed supplies helped.

-- Late in September, Nazis having been cleared from her area, she and several British and American officers working for her arrived in Paris. Not long after, she relocated to Austria, again to foment anti-Nazi resistance. Back to Paris, April 1945.

Judith Pearson writes history not simply with a command of facts, but with a keen sense of the drama that often lies behind them. She likes to end chapters with a punch, of which

the ambulance-driving chapter with Claire de la Tour is but one example. The title of the book comes from the last line in the Prologue, where Virginia and Henri, back in France and in

disguise, walk five miles to a small town along Brittany’s rocky coast, catch a train to Paris and proceed several hours directly south, to Crozant, where a Resistance sympathizer

provides her with a shack lacking not only electricity but running water. Henri returns to Paris. She takes up duties cooking meals for the family and pasturing the cows -- and for the OSS,

using the Type 3 Mark II transceiver she has lugged all this way in a suitcase. One day, making her way through town to the farm, she sees a small crowd and discovers they are viewing

three men and a woman hung from iron fence posts, spiked through the neck. The Nazi soldiers want villagers to know what happens to those who dare resist the Führer. Virginia uses her

btransceiver for a last message from this location. “Its meaning would be understood by the few with a need to know: ‘THE WOLVES ARE AT THE DOOR.”

MORE-cont.

The Woman Who Smashed Codes:

A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine Who Outwitted America's Enemies

by Jason Fagone (2017)

Scotland Yard saved the day. In 1917, an officer had been directed to the cipher school at Riverbank by the Dept. of Justice because he had a packet of messages in code and he

needed help. He suspected they involved a group of Hindus who wanted to separate India from the UK. Elizabeth and William set to work. They proved he was right. Arrests were made.

Elizabeth was called to testify at a trial in SF, but before she could enter the courtroom, a Hindu in the balcony stood up and started firing shots -- he was trying to kill the defendants

because he thought they’d betrayed the cause.

The Elizebeth-William duo learned a lot about ciphers. (They married 5/1917).

All this brought them to the attention of the U.S. military. The US finally joined in the Great War in 1917, but it had no effective intelligence services. The Military

Intelligence Division in the War Department was badly underfunded. (The famous January 1917 telegram from Germany’s foreign minister, Herr Zimmerman, to Mexico, urging it to attack

the US with German aid, was decrypted by the British). Outside the military, there were few people in the country with codebreaking knowledge. Sensibly, MID recruited Elizebeth and

William and -- eventually -- parted them from Riverbank.

William soon joined the army and was sent to France to work on ciphers. After the war, he disappeared into Army cryptology in DC, she into Coast Guard crytology (CG was then a

civilian agency). Prohibition had engendered a remarkably extensive network of rum-runners, all of whom encrypted their messages, a network with which the CG had to deal. Elizabeth

broke them all, and, perhaps even more remarkable, managed to persuade the CG to provide her with enough money to create a small unit dedicated to this task.

In WW2, William’s work on WW2 codes was so secret that he could not even discuss it with his wife. (His unit matched the more famous Bletchley when it came to Nazi codes, and it

broke the Japanese codes, called Purple, as well -- the actual codebreaker being another woman, Genevieve Grotjan, about whom a book should be written). She, in turn, did not discuss

her work with him, as he had enough codebreaking on his mind. (Indeed, it increasingly weighed him down, exacerbating depressions to which he’d long been prone, creating other mental

difficulties as well; at one point he received electroshock therapy).

Repeal of Prohibition in 1934 did not put an end to Elizebeth’s codebreaking. Rum-runners merely transitioned into drug dealers. That occupied her up until Pearl Harbor. CG was

now militarized, and her focus soon became Latin America. Nazi efforts there, almost all of which were conducted in secret, were extensive and should be better known. FDR was very

concerned that Hitler would turn these countries against the US, and he ultimately signed an Executive Order creating authority to deal with the problem. Unfortunately, he gave the

authority to J. Edgar Hoover, head of an agency which had no experience in the area and no expertise at all in codebreaking. Hoover, moreover, was uncomfortable working with

women, but his only option was to rely on Elizabeth. Although he found the codebreaking of her unit vital, he repeatedly, and on many occasions, made it appear that every success

was entirely the work of the FBI.

(This is not in this book, but it is in The Train to Crystal City by Jan Jarboe Russell, about the US internment camp in TX. One of Hoover’s actions was in Peru -- he rounded up

everyone of Japanese extraction living there and shipped them off to Crystal City).

In fact, Elizebeth and her little team read all of the messages transmitted from and to Latin America. The leader of the Nazi effort was Johannes Siegfried Becker, who developed

close ties with Juan Peron -- so close that even after the war when Nazi-hunting began, Becker was able to disappear and was never found. But Becker’s technical officer was Gustave

Utzinger (real name Wolf Emil Franczok) “a twenty-six-year-old man with short brown hair and a Ph.D.” in chemistry. Utzinger had gained experience in coding and radio transmission in

the navy before he joined the SS. One paragraph about the summer of 1943 sums up Elizebeth’s mastery:

Becker wasn’t alone in his miscalculation that summer. Gustave Utzinger, the ring’s radio expert, was also failing to grasp the danger of his position. The Americans -- Elizebeth

Friedman and her team -- had broken his cipher machine and were now reading his every transmission, but for Utzinger, the prospect of a Yankee breaking an Enigma machine was

beyond his comprehension.

Imagine the shock when he found it was a woman!

In January 1944 the whole Nazi network was rounded up, and J. Edgar took the credit.

“She crossed the street [Nebraska Ave], paused for a few seconds, and looked back at the grubby, flat-roofed building where she had spent her war.” This was 1946. Her

following years were not so eventful. How could they be? For this she was no doubt grateful. Much of her time was spent dealing with her husband’s illnesses. William died in 1969. His

death was a big event, Arlington Cemetery, Honor Guard. Eugene McCarthy attended because Eugene had worked during the war on William’s team for a while. Elizebeth’s death was

far less noticed. The Washington Post and The New York Times published short, respectful obituaries, but neither mentioned her feats of code-breaking. They couldn’t

though, because her work was not declassified until two decades later. One of the great things about Fagone’s book is the feeling when you finish that finally justice is being done.

STILL MORE-cont.

elifesciences.org

The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee (2016)

In 1926, after two failed attempts with higher doses, future Nobel Laureate Hermann Muller discovered that extremely low doses of radiation could create genetic mutations. In fruit flies.

"It was late at night, and the only person to receive the breaking news was a lone botanist working on the floor below. Each time Muller found a new mutant, he shouted down from the window, 'I got another.'"

This was in Texas. Muller, from NYC, had been offered a position there at what later became Rice University by Julian Huxley.

Muller was a left-winger, had joined socialist groups, and he took this to Texas. There he edited a newspaper, The Spark, which advocated civil rights, education for immigrants, collective insurance for workers. The college administrators were not in favor of socialism. He was investigated by the FBI. "Newspapers referred to him as a subversive, a commie, a Red nut, a Soviet sympathizer, a freak."

"Isolated, embittered, increasingly paranoid and depressed, Muller disappeared from his lab one morning and could not be found in his classroom. A search party of graduate students found him hours later, wandering in the woods in the outskirts of Austin. He was walking in a daze, his clothes wrinkled from the drizzle of rain, his face splattered with mud, his shins scratched. He had swallowed a roll of barbiturates in an attempt to commit suicide, but had slept them off by a tree. The next morning, he returned sheepishly to his class."

Sick of America, he looked for a place where science and socialism would go together, where egalitarianism existed, merit being the sole criterion -- the Weimar Republic. And Berlin, an intellectual city. "In the winter of 1932, Muller packed his bags, shipped off several hundred strains of flies, ten thousand glass tubes, a thousand glass bottles, one microscope, two bicycles, and a '32 Ford -- and left for the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. He had no inkling that his adopted city would, indeed, witness the unleashing of the new science of genetics, but in its most grisly form in history."

This is but one of an incredible number of fascinating stories that populate Siddhartha Mukherjee's incredibly great book. From Aristotle to Mendel and Darwin, Nettie Stevens (XX XY), Morgan and Muller, Dobhzansky, Crick and Watson, Paul Berg (Siddhartha's PhD advisor, recombinant DNA pioneer), Herb Boyer (Genentech) -- programmed cell death -- the sex gene -- Craig Ventnor -- Jennifer Doudna (CRISPR) -- that and much more. The bad guys are all here as well (as are all our diseases), and it's not just Nazis. Brits and Americans promoted versions of eugenics. Don't leave out Buck v. Bell and Holmes' "Three generations of imbeciles is enough." The whole eugenics movement is treated in mesmerizing detail, as is, in an entirely different vein, the role that genes play in creation of personality.

Siddhartha was born in 1970 in Delhi to Bengali parents, whose own families were greatly affected by The Partition. His mother had an identical twin; his father's siblings and their progeny suffered from various genetic disorders. He has a personal stake in genes, some of this woven into the book. He also has a personal stake in genetic research (he is also an M.D.) -- and is a leading researcher into T cells. Where he finds time to write books like this, and his other incredibly great book, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, is almost beyond comprehension. Somehow, he has also managed to learn everything about American culture, bringing up Wonder Bread, Rube Goldberg, and many other things as if they were commonplace in Delhi.

He is also a wonderfully likeable person. After explaining the research that led to the unbelievable conclusion that the entire human race is descended from people who lived in southern Africa a hundred or two hundred thousand years ago (the "oldest human populations -- their genomes peppered with diverse and ancient variations -- are the San tribes of South Africa, Namibia, and Botswana, and Mbuti Pygmies, who live deep in the Ituri forest in the Congo"), he recounts his own journey to these regions in 1994 as a grad student, travelling the Rift Valley from Kenya to Zimbabwe, crossing the Zambezi river to the plains of South Africa, encountering an arid mesa where some of the San tribes once lived.

"It was a place of lunar desolation -- a flat, dry tabletop of land decapitated by some geophysically vengeful force and perched above the plains below. By then, a series of thefts and losses had whittled my possessions down to virtually nothing: four pairs of boxers, which I often doubled up and wore as shorts, a box of protein bars, and bottled water. Naked we come the Bible suggests; I was almost there."