MENTAL FETTLE °

Books/plays/movies/&. 59ers: Review something! Send to class gmail address. For sci/tech mental exercise there's now our highly-eclectic, richly-variegated F3 page.

Carl Djerassi's autobiography. (1992)

The name may not be familiar, yet it's hard to think of anyone -- anyone at all -- who has had a greater impact on the personal lives of the Class of 59 than this man. Indeed, not just our class, but all classes, everywhere, starting about the time we were on the Hilltop and continuing right up to present day!

Djerassi was the father of the pill.

This book tells the pill's story -- and Djerassi's, beginning with:

"Arriving at our Gasthof, we sit down for lunch. The choices in our small inn are limited to various Schnitzel. At the sight of my Naturschnitzel mit Champignons, drowned in cream sauce, the Viennese in me salivates, even as the weight-conscious, lipophobic Californian draws back in horror.”

There's a lot in this paragraph, the third in the book. As the fondness for cream sauce indicates, he was born in Vienna -- in 1923, it should be added. His mother was Austrian, family name Friedmann, a doctor and a dentist. His father, a dermatologist who specialized in treating syphilis (before penicillin, one wealthy guy with the disease could provide a year's income) was from Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria.

So, this was a union, an unusual one. It was a union of two very different Jewish cultures. The culture based in Central Europe is Ashkenazi and speaks German-derived Yiddish. The US today has 5 to 6 million citizens who trace their ancestry to this culture, twice as many as in Israel. The other is Sephardic, the culture of the

Sephardim. These speak Spanish-derived Ladino and established themselves in Spain and Portugal -- until expelled near the end of the 15th century. Some, it seems, ended up in Bulgaria.

Not surprisingly, there was a divorce when Carl was a child. His parents hid the divorce from him till he was in his early teens. He lived with his mother in Vienna, but summered with his father in Sofia. In 1938, his father remarried his mother, so she and Carl could escape the takeover of Austria by the Nazis, the Anschluss -- and survive! Few of us know much about Bulgaria, but here is something to know: "although not immune to antisemitism, Bulgaria proved a safe haven, as the country managed to save its entire 48,000-strong Jewish population from deportation to Nazi concentration camps." Truly remarkable.

Traveling regularly between the two cultures, Carl found that he much preferred the Sephardim. These people were more laid back and enjoyed life more. The Ashkenazi, at least in the form presented by his mother, were tense and driven, with few pleasures.

Not lucky enough to become a Hilltopper, he benefited from the next best thing -- in the circumstances. His father had him attend the American College of Sofia for a year, where he became fluent in English. Other than that, he had a fairly regular upbringing. He joined the Boy Scouts, learned Morse code, used it to convey exam answers to friends (two thumbs up, dash, one, dot)

In December of 1939, he and his mother arrived in NYC, "nearly penniless." It saved his life. He was sixteen. His mother found a job in upstate NY, near the Canadian border, while he was placed with a wonderful volunteer family near the city. His father stayed in Bulgaria and managed to survive only because of that country's remarkable achievement. Carl did not see him for many years.

Although he hadn't graduated high school, he ended up at Newark Junior College, where he was inspired by his freshman chemistry teacher, Nathan Washton. Approaching graduation, he wanted to continue at NYU -- so he wrote Eleanor Roosevelt. He originally thought to address her as "Your Excellency." He hoped she could help him get a scholarship.

He ended up with a scholarship to Tarkio College in MO. One you've never heard of, but in fact it has one very famous chemistry graduate, Wallace Carothers, who invented nylon. (Alas, he committed suicide a few years after). Carl found that he was a great novelty in the area -- someone who has come from the very maw of what everyone suspected was heading to become a worldwide catastrophe. Rotary clubs asked him to speak on the “European situation” – he stole from John Gunther’s book, Inside Europe, including his definition of Balkan Revolutions ("abrupt changes in the form of misgovernment"). Carl had an accent, which he enhanced because he knew it added to his appeal. When he lectured in churches, they passed the collection plate and give him whatever was in it (except the Methodists).

On his way to visit his mother, he stopped at Kenyon. Loved it. Applied. "I was offered a room, board, and tuition scholarship." He entered as a junior, but took an especially heavy course load, and graduated in one year summa cum laude. He then turned 19.

He did eventually make it to upstate NY, near the Canadian border, to see his mother, and while sitting around in her clinic, waiting for her, he glanced through the promotional materials from pharmaceutical companies lying about. He had already decided against an M.D., having read Paul de Kruif's Microbe Hunters. What he found in those materials can be said to have sparked the pill -- not because of any science they contained, but because he realized how many pharma firms were based in NJ, not far from Newark, "my emotional American home." He wrote them all, and one, the American branch of Switzerland's CIBA, offered him a job. "It was in Summit, New Jersey, that I crossed my Rubicon into organic chemistry."

At CIBA he worked with another Viennese refugee, twenty years older, and they "discovered one of the first antihistamines," Pyribenzamine, which quickly became the drug of choice for allergy sufferers and was used by millions. He is still only 19.

After this he read a famous natural products (drugs derived from plants and other organic materials) book and became hooked on steroids, in particular. He also decided to get a PhD in organic chemistry, applying to and accepted by Wisconsin.

He worked under two young profs seeking "the total synthesis of steroids," though he also did research into transforming steroids into drugs of use. He got married (first of three), still only 19, on his way to Wisconsin (wedding night on Pullman sleeper), and while there had one of his knees fused to solve a longstanding problem. He got his PhD in two -- two! -- years.

Back to CIBA. His book contains a diagram of what he calls the "steroid skeleton," showing where carbon and hydrogen atoms are placed, and also what the diagram looks like when a third atom, oxygen, is added.

"Many of the most important biologically active molecules in nature, indeed, represent slight variations on the steroid skeleton: the male and female sex hormones, bile acids, cholesterol, vitamin D, the cardiac-active constituents of digitalis, the adrenal cortical hormones (related to cortisone and usually referred to generically as 'corticosteroids')."

He wanted to work on synthesizing cortisone, but that was monopolized by the people in Switzerland. Eventually, a colleague suggested he apply as associate director of research at Syntex, in Mexico City. There he found yet another refugee, George Rosenkranz, about a decade older and from Hungary, who was director of technical research. A large project was synthesizing cortisone, and Carl would head the research group. Cortisone was being looked upon, after the war, as a wonder drug, relief for arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. It could be produced -- after 36 steps, and great expense -- from the bile of slaughterhouse animals, but synthesis was the way forward. And the way forward was a great race among the pharma giants, all mammoths compared to that tiny mouse, Syntex.

But Syntex had young Mexican women technicians who'd joined the lab after grammar school. Carl soon learned to appreciate their advantages. They knew the "necessary chemical operations" and produced the needed result on time. They also innovated usefully on occasion. More advanced work was undertaken by undergrads, mostly women, from National University of Mexico. For the university, they had to produce a thesis, and this could be work at Syntex in remarkably well-equipped labs. Some of this led to publications in renowned academic journals by these young scholars.

Carl describes all this, the race to synthesize cortisone, using a mountain-climbing metaphor. The summit is synthesis. The final assault is all men, including an Oxford-trained Mexican organic chemist, Octavio Mancera, top prof Jesus Romo. and another Hungarian refugee, Juan Pataki. Rosenkranz and Djerassi are the expedition leaders.

His description of their three-pronged attack is too technical in its details and for this review, but he enlivens it with the fact that they had a mole in the labs of a major competitor at Harvard -- the mole was a grad student engaged to "a beautiful Mexican chemist."

An important aspect was utilizing something which had been discovered by the man who founded Syntex, Russell Marker, a chemistry professor at Penn State. Marker had discovered that substances in certain plants, inedible yams, could be easily transformed chemically into the female sex hormone progesterone. These yams grew in Mexico. Marker soon left his company, but his work lived on and ultimately provided a foundation for the ascent up the mountain.

One way to describe the ascent is that the leaders were discovering new paths in the structure of the steroid skeleton, publishing each advance in prestigious journals and, for the first time in its history, gaining some credit for science in Mexico. Ultimately, all of these paths resulted in a kind of convergence, and Syntex and its expeditionary leaders were able to stand at the summit, the first to arrive, beating out Harvard. One important proof of their success is described in the first paragraph of chapter 4 -- and in its title, "No Depression." They had sent a sample of their synthetic creation to a Nobel Laureate in Switzerland to mix with the stuff laboriously extracted from those slaughterhouse animals. The telegram which came back contained the two words in the chapter title, and what they meant was that the synthetic stuff was just as good as the extracted stuff.

They published their details and their results immediately. Carl goes into some of the fine points of academic priority in the most prestigious of the journals, but Life, Newsweek and Harper's, in the summer of 1951, had no trouble figuring out who was first. Life, in particular, featured a large photo of the Syntex team (Carl was 27, similar in age to the others, half with Mexican names) sitting at a conference table, the centerpiece of which is a large bag of yams. "CORTISONE FROM GIANT YAM."

The higher mountain in the distance, however, still needs climbing. At this point Carl addresses the claim that he is the father of the pill. Not so simple, he says. In fact, it's a bit like a family:

> father – organic chemist, produce substance

>mother – biologist, demonstrate activity in animals

>midwife – clinician administers to patients

And progesterone leads the way. One of its qualities is that when a woman is pregnant, progesterone prevents ovulation from occurring. So, it has contraceptive capabilities. The problem was to synthesize it in a form which would overcome its limitations as an oral contraceptive. Again, the details of the synthesis are complex, but by 1953-4, the substance Syntex produced, together with a very similar substance developed by G.D. Searle & Co., was being tested for anti-ovulation properties, tested successfully. Syntex chose to partner with Parke-Davis as a marketing organization.

In 1957, both the Syntex-PD and Searle products were approved, and on the market -- but only for menstrual disorders. In 1958, PD got cold feet about marketing something as controversial, in their view, as a contraceptive. At this point, Syntex's Alex Zaffaroni, a 27-year-old native of Uruguay with a PhD from the University of Rochester, led the company to J&J because it already marketed contraceptive devices. There was a delay in redoing certain studies, because PD refused to give up data, with the result that Syntex was on the market two years after Searle. But by then PD had awakened and joined in with Syntex and J&J. This triumvirate soon led the market.

Carl says he is proud of his role in the sexual revolution of the time -- and that he never received any royalty on sales of the pill. His shares in Syntex, however, made him a rich man, and the bulk of his book deals with a number of other adventures in which he became involved, some of them, such as art collection, promotion of the arts, and becoming a Dapper Dan, due to his wealth. These are all interesting, often highly amusing, and the story is very well told. There is also a magnificent chapter on the state of birth control in the world fifty years after the birth of the pill.

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History

by John M. Barry (2009)

Why Should Anyone Care About a Pandemic That Happened A Hundred Years Ago?

I picked up a copy of this book some years ago. My father’s younger brother Val died of the Spanish flu in 1918. That was mentioned from time to time in the family, but neither my father nor my grandparents ever talked about the Spanish flu itself, not even why it was called the Spanish flu. The book sat on my bookshelf for many years. It was thick and seemed likely to be depressing.

The obvious circumstances spurred me to dive into the book this spring. This review is written for people who, like me, read reviews mostly to decide whether they might like to read a book. There are much longer reviews – the NYRB essay runs almost 5,000 words – for anyone who wants a soup-to-nuts analysis of the book from every angle. So, prosaically, this review will talk only about why you might like The Great Influenza, and the reasons why you might not like it or be thoroughly sold on some of it. And consistently with the goal of motivating people to read this excellent book, this review will try to avoid spoilers, with one exception.

As for reasons to like the book, the author, a self-taught but respected historian, describes how the Spanish flu first surfaced in Haskell County, Kansas in March 1918. After a brief and not overly troubling run through several military camps in the United States and France, the outbreak largely disappeared. It came roaring back in the fall in a frighteningly more lethal form, appearing simultaneously in Brest, France – the major port for disembarkation of American troops being rushed to fight in World War I – and on the East Coast of the United States. Within a matter of weeks it killed most of the roughly 700,000 people who would die in the United States, and of the 20 million or more who died worldwide.

Perfect reading, obviously, for anyone staying home because of the coronavirus and the COVID-19 disease. The parallels – and, more frighteningly, the possible parallels – are many. In 1918, the public response was distorted, or worse, by politicians with personal agendas. President Wilson was fixated upon sending a maximum expeditionary force to France in the shortest possible time. So conscripts were crowded – jammed, really – into military cantonments that created the worst possible conditions for the Spanish flu to spread. Senior military officers rejected the pleas of public health officials because they gave primacy to Washington’s political goals. In Philadelphia, the frenzy to sell war bonds caused local politicians to insist upon going forward with a massive rally after the flu had arrived there, with disastrous consequences.

The book presents a detailed and graphic account of what happened when the health care system was overwhelmed by an “invisible enemy” in places such as Fort Devens outside Boston and in Philadelphia. The terror of soldiers and citizens suffering these conditions are matched against the assurances of their leaders – contrary to on the ground evidence – that the epidemic was well under control, or would be within days. The heroism of health care workers is described while they struggle to care for the living (and dispose of the dead) with wholly inadequate resources. Until, in some places, the health care system simply crumbled.

The Great Influenza puts paid to any fanciful notion that “No one could have foreseen anything like” the coronavirus pandemic. It also paints on the broader canvas of the history of medical science and medical practice from the late 19th Century to the first decades of the 20th. The limits of medical knowledge in the decades before the Spanish flu, the incredible inadequacies of all but a few medical schools, and the incompetence or worse of most medical doctors has been written about many times. But it provides important context for what the medical world was like at the time of the Spanish flu. It also provides a sharp contrast with conditions today, of course.

In addition to this history, The Great Influenza also portrays to dramatic effect the efforts of the leading scientists of the time to combat that pandemic. The conditions were horrible. Their resources were inexcusably limited. And it was not a success story. Vast effort was expended on the assumption, and it was largely an assumption, that the influenza was caused by bacteria. A decade before, Paul Lewis had shown that polio was caused by a virus, and developed a vaccine that was highly effective in monkeys – although it took decades to develop a human vaccine, a cautionary note for those today who insist a coronavirus vaccine is just around the corner. But even Lewis was drawn down the bacterial rabbit hole. No one figured out that influenza was caused by a virus, too, until well after the pandemic was over.

But the story of how these scientists struggled to solve the Spanish flu mystery is fascinating. For those who have never dealt with bacterial microbiology and virology, it provides a useful primer to begin to understand the issues confronting researchers today. For example, an effective vaccine against the coronavirus seems much more likely than the notoriously erratic influenza vaccines developed for every flu season. But the delicacy of vaccine development and production make an effective vaccine problematical, and doubtful in the very short term.

With all this going for it, what is not to like with The Great Influenza? For one thing, the book’s organization and efforts to follow the careers of a generation of leading scientists can be somewhat off-putting. Barry writes fluidly and well in an unpretentious manner. But chapters that alternate between what was happening with the pandemic and the medical research saga can make it hard to follow either line. Trying to keep track of the research projects and career development of so many scientists can also be wearing.

The author’s largely Manichean view of his characters may also be overdone. Even for someone generally suspicious of politicians and critical of the military mind, the portrayal of those classes may seem too unremittingly negative. The scientists, on the other hand, are largely portrayed as a noble, selfless band, intent only on joint pursuit of the scientific goal. The gritty portrayal in Watson’s The Double Helix of races to publish first and other one-upmanship seems more realistic, or at least provides a more balanced view.

Finally, although the author is unquestionably knowledgeable about his science, he may be led astray in explaining the end of the pandemic. After a painful rebound in 1920, it disappeared. And in moving from the East Coast to other areas of the country, the Spanish flu arguably became weaker and weaker. The author attributes this to a “reversion to the mean.” He theorizes that the virus that struck so hard in the fall of 1918 was an “extreme” mutation, which carried the likelihood that subsequent mutations were likely to carry it back toward a normal influenza virus. In fairness, Barry presents this as “not a law, only a probability.” But, like at least one recent and well-publicized effort to portray the coronavirus outbreak as a self-limiting phenomenon that could dependably be expected to result in only a limited number of deaths, efforts to assume such predictability in the dangerous and incompletely understood world of virology seem at best facile.

NOTE: So what is the spoiler? It is where the name “Spanish flu” came from. No, the outbreak did not first appear in Spain. Far from it, as explained earlier. What happened was that the American, French, English and even the German press were widely censored or self-censored themselves into not mentioning the flu outbreak and epidemic to avoid harming morale and the war effort. Spain, however, was neutral in the first world war, so its press freely discussed the flu, especially when King Alphonse XIII became seriously ill. So the outbreak became known as the “Spanish” flu.

Review by classmate amigo.

° MORE °

February 22,2024

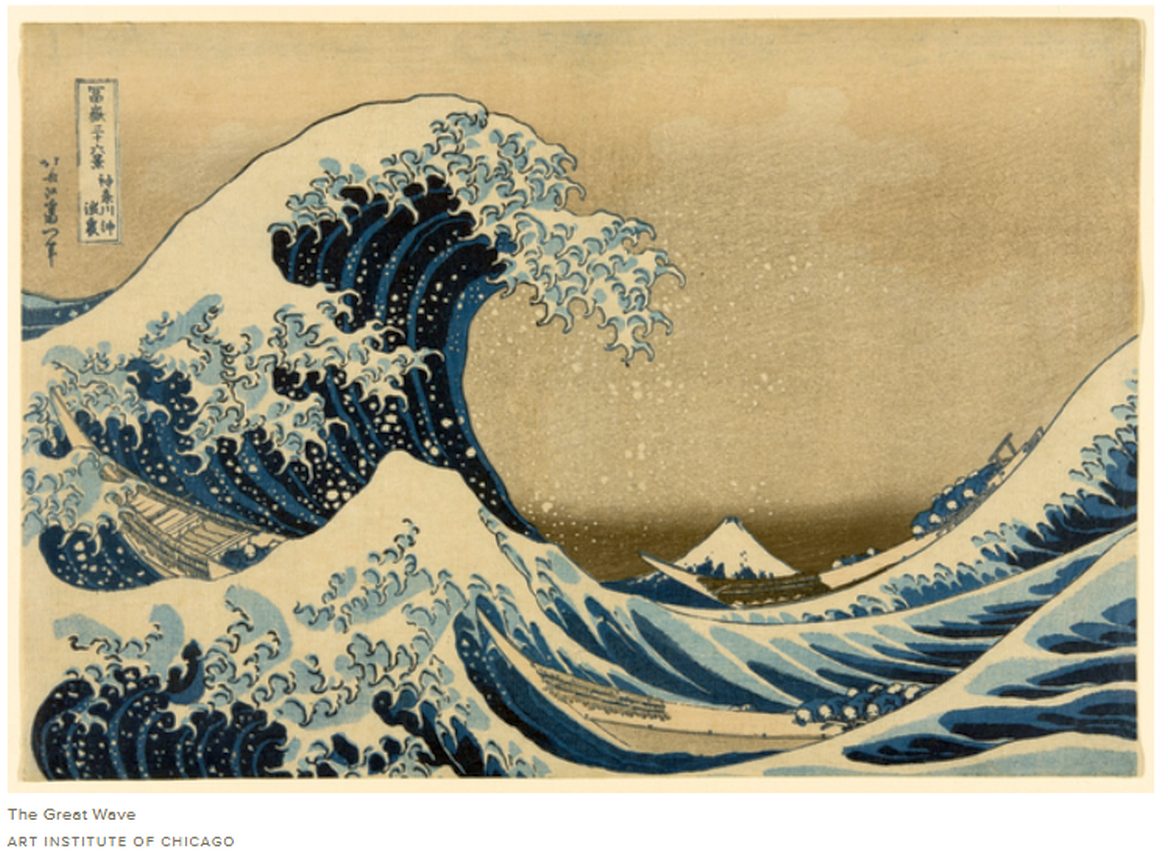

The Great Wave Washes Up by Lake Michigan, by Grace Ramsey, Social Media Editor, November 22, 2024

Hokusai's Great WaveStudent pit orchestra brings undead ‘Addams Family’ musical to life by Addie Williams, Staff Writer, November 12, 2024.

Instructional Coach by Isaac Guerrero, Columnist November 4, 2024b

First Semester, New English teacher, Soon Dean. by Amy Tran March 23,2022

"Growing up on the West side of Chicago, Mrs. G had a big passion for teaching. From watching TV to her personal experiences in school, she had always thought that teaching was the role for her. Specifically, she recalls role-playing as the teacher while playing “school” with her cousins as kids: “I was literally the teacher. I was always the teacher.” It didn’t occur to her until high school, however, that she wanted to become an English teacher." More here.

Chloé Zhao’s Eternals Wows Audiences

by Sam Schoettle, Sports Ed. 11-10-2021

What do you get when you combine the most successful franchise of all time, an Academy Award winning director, a 200 million dollar budget, and a cast stacked with the likes of Angelina Jolie, Hallyuwood’s Don Lee, Salma Hayek, comedian Kumail Nanjiani, Game of Thrones’ Kit Harrington and Richard Madden?

The Eternals.

Chloé Zhao, the aforementioned award winning director has taken her talents from independent films such as Nomadland to the big budget of a Marvel Studios film. The film is based on a group of immortal beings from comics made by Jack Kirby, a famed Marvel writer from the past. Zhao’s film style is unique, in that she shoots much of her film on site – a difference from the green and blue screens Marvel so frequently uses.

The Eternals consist of 10 members:

- Ikaris (has the ability to shoot cosmic beams from his eyes; leader and the strongest)

- Sersi (has the ability to manipulate matter)

- Thena (has the ability to create and master weapons)

- Gilgamesh (has the ability to produce an exoskeleton of cosmic energy)

- Phastos (has the ability to create and design)

- Sprite (has the ability to create illusions and disguise; can manipulate matter to a lesser extent then Sersi)

- Druig (has the ability of mind control)

- Makkari (has the ability of super speed)

- Kingo (has the ability to shoot cosmic blasts)

- Ajak (has the ability to heal others; ‘mother-figure’)

Regarding the plot, The Eternals was fast paced – for a movie clocking in at a little over two and a half hours, the film itself felt much shorter. It opens showing the return of the deviants to earth, as the Eternals ‘get the band back together’. During the rising actions, we see how throughout history the Eternals have progressed humanity forward, in events both successful and dreary. Once the band is back together, tensions flare, and sides are drawn as shocking information is revealed. Will this family-like team stick together, or cave to such a quarrel?

All-in-all, Chloé Zhao’s The Eternals was a blast; I highly recommend any reading to watch!

Here's a link to the trailer.

Mystery Must-Reads

Find a mystery novel or series that will let you imagine yourself as a vital part of its plot, and let you feel the thrill of solving a case.

by Michelle Bishka, Features Editor

The only time life as a high-schooler has the intrigue of a mystery novel is when that high-schooler belongs to the fictional world. Although not everyone can be a character in a book, everyone has the opportunity to explore the many mystery novels that can give them the same buzz of solving a crime. Browse the list below to find a novel or a series to fulfill your mystery reading needs.

1. In the Woods, Tana French: “What I am telling you, before you begin my story, is this – two things: I crave truth. And I lie.” Tana French is a novelist who is famous for her enticing plots that keep her readers guessing, and In the Woods is no exception. In the Woods marks the start of a series following a group of detectives that call themselves “The Dublin Murder Squad.” The book begins by describing a case that happened many years ago: the kidnapping and murder of a group of children in a forest. One child remained alive, Rob Ryan, but he was unable to remember what happened that night or who was responsible for the crime. Many years later, a similar case emerges, and Rob, as part of “The Dublin Murder Squad,” is on it to finally discover who is responsible, and to find closure for himself. However, it proves to be difficult for Rob to relive his past, and he keeps it a secret from the rest of his partners on the case. French does an exceptional job at painting Rob as a severely flawed character who still remains likable no matter how much unintentional harm he does. This is because Rob is not a horrible character, but a lost one. Instead of hating the main character for the damage he does, it makes you sympathize with him. With complex characters leading this novel, In the Woods is not one to miss.

2. The Dark Lake, Sara Bailey: A thriller rivaling Tana French’s work, The Dark Lake revolves around Gemma, a detective cracking the case of the murder of a young teacher named Rosalind, who she knew from high school. Although Rosalind was adored in high school, Gemma fostered some darker thoughts about her. Her obsession with Rosalind in the past spills over to the present in ways you would never expect until you have read the novel. Although Gemma has an unnerving perspective on the case, and makes many mistakes throughout the book, she is not a character to be hated, but she is not one to be liked neither. With its psychological approach to crime, The Dark Lake is definitely not a thriller to skip.

3. The Cuckoo’s Calling, Robert Galbraith: Written by J.K Rowling under a pseudonym, this novel, based on another traditional thriller plot, sparks a new series dubbed Cormoran Strike. The whole series follows Detective Cormoran Strike who was contacted to solve a case as a private investigator after being out of work for quite some time. The first novel deals with a murder of a model that has been staged as a suicide. Despite the fact that the plot may seem appealing, the storyline does tend to lag in some places, and the writing style may not be up to everyone’s taste. Although this was a solid start to the series, I prefer the second novel of the series the most, The Silkworm, as its plot reveals to be more fast-paced.

4. Dangerous Girls, Abigail Haas: “Wouldn’t we all look guilty, if someone searched hard enough?” Dangerous Girls is a dark mystery that is a bit contradictory, making it even more enjoyable. The novel inspects the unpleasant side of friendships closely, to the point where it seems that the safer alternative to making friends is to avoid people altogether. However, while showing the nasty corners of friendship, the book shows the importance of friendship as well. These mixed signals Dangerous Girls sends the reader is part of the reason the novel is viewed so highly in addition to its exceptional plot. The plot follows Anna and her friends on their trip to Aruba for spring break. Unfortunately, what was intended to be a trip about having fun, instantly transforms into a disaster involving a murder case that leaves Anna to be seen as its prime suspect. The story progresses quickly due to the writing style of the novel: the book moves forwards and backwards in time. This haphazard approach to writing ultimately adds to the effect of the story.

Hopefully one of these books or series will let you visualize yourself as a character in its plot, and let you feel the excitement of cracking a case.

About Michelle.

And thanks to The Glen Bard for the above reviews. They keep us up-to-date!

Here are links to other of their reviews of interest: Jojo Rabbit

[a comedy about the Hitler youth][remarkable]; and

Best documentaries.

Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher, and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize

by Sean B. Carroll (2013)

A riveting story that weaves together an account of two now-famous Frenchmen, in two very different intellectual fields, and their roles in the French Resistance in German-occupied France during World War II: Albert Camus and Jacques Monod.

The book can be read as a history of the war from the French point of view, and is fascinating from that perspective alone. But the book also deals extensively with the postwar careers of these two men (who came to know each other), during which each won the Nobel Prize.

Camus, writer and philosopher, the more likely of the two to be known to the general reader, is known for his novels The Stranger and The Plague as well as other works

such as The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel. He was the editorialist for the underground newspaper Combat, secreting himself and his partisan colleagues in

Nazi-occupied Paris.

Jacques Monod, a pioneering molecular biologist at the Pasteur Institute, was a member of the militant partisan group Franc-Tireurs et Partisans. The author describes events in

occupied France and how these men risked their lives.

Monod is perhaps of special interest to 59ers because although he was born in Paris and was thoroughly French, his mother was from Milwaukee. Her name was Charlotte (Sharlie)

MacGregor Todd, of Scottish extraction. His French Huguenot father, Lucien, was a painter and inspired the son artistically and intellectually.

Though born in Algeria, Camus was a French citizen, because his grandfather had moved there from France. His mother's relatives were from the

Balearic Islands.

His father, another Lucien, was an agricultural worker, killed in the Battle of the Marne during WW1 (Camus never knew him).

Following the War, they resumed their careers. Camus received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1957. Monod, together with colleagues Francois Jacob and Andre Lwoff, described the

genetic regulatory mechanisms in protein synthesis. These three received the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology in 1965. Camus was killed in an automobile accident in 1960 at the

age of 46; Monod died of leukemia at the age of 66. The two men knew each other and were friends.

Brave Genius details Camus’ philosophy and writing, giving glimpses of his private life. It also relates the scientific issues leading to Monod’s seminal studies (for

non-scientists, there is a useful Appendix) and a brief biography. Packed into this rich material are fascinating post-War stories, including Camus’ falling out with Jean-Paul Sartre,

Camus’ critique of Communism, Monod’s critique of Soviet pseudo-science (Lysenkoism), and his support for and participation with the rebellious students in 1968 France. Especially noteworthy is Monod’s role in helping two scientists escape from Hungary after 1956, when Russian tanks rolled in.

This is an enthralling book and well worth the effort in reading its 500 pages -- in fact it is no effort at all.

PS: the author is a molecular biologist and geneticist who became a Francophile when one of his professors at Washington University in St. Louis suggested he do some

reading about French scientific work. He teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. (He's also a first-class war historian.)

Olives: The Life and Lore of a Noble Fruit by Mort Rosenblum (1996)

Mort, in the 1980s, living in France and working for the European edition of the NY Times, bought a "little ruin in a back corner of high Provence." "It took a day's hacking just to reach the collapsed house." On his new farm, he discovered that two hundred olive trees "lurked somewhere out there in the jungle."

Mort knew nothing of olives. But that discovery led to an obsession with this noble fruit, one which began with his own hacking and which he later was able to pursue in depth because his brief at the Times included economic matters -- this enabled him to travel in the area of the Mediterranean to wherever olives are grown commercially. It is these travels and the descriptions of what role olives play in cultures that are the heart of the book. Spain is the world's largest producer (600,000 tons), twice as much as Italy #2 -- France a mere 2,000. Spain's production methods date back thousands of years; even the slightest modernization produces profuse apology. Tunisia is a major producer, much of it sold to Italy where it is repackaged and labeled "Product of Italy." Olive trees are inherited in Tunisia, so that after many generations a son might own a single branch.

One review found on the internet says: "What I learned from this book: that most of the olive oil industry is corrupt, that the most corrupt are the Italians who import olive oil world wide and export it as Italian olive oil, that most commercial oil is treated with chemicals . . . ." That's one interpretation.

Mort tells us about labels and standards:

"Extra-virgin" = "free fatty acids -- mostly oleic acid -- is below 1 percent. Also, the organoleptic properties -- taste, aroma, feel on the tongue -- must rate high." Freshly-squeezed by first-press or cold-press. "Plain olive oil, often marked 'pure'" = "refined inferior stuff best kept for frying." It is "rectified" with steam and chemicals, then mixed with its betters for some flavor and aroma. "Pomace oil" = comes from first press leavings, refined to lower acidity below that of lamp oil.

Canned olives? Ugh! You can't eat olives straight off the tree; they need to be cured. "The industrial method produces those canned

'black ripe' globules [he won't call them olives] graded from huge to humongous. Doused in

caustic soda for a quick cure, and bubbled with an iron compound for color, little remains of taste or texture."

(Incidentally, as to labels, UC Davis, founded originally as an ag school and even today alma mater of California vintners, did a study in 2010 where they bought olive oils labeled "Extra virgin" off supermarket shelves, then evaluated them. The results were shocking enough but there's been a lot of overinterpretation, including false claims that adulteration and cutting were

found. The study is hard to find these days (wonder why), [this was the original link]: UCD,

but the summary in the press release at the time can still be found and we have it: here. And the study was sponsored by producers of California olive oil --

which came off best -- who no doubt felt that foreign imports were misrepresenting themselves as to quality.)

The best part of Mort's book, though, is the first chapter, a history of olives, with anecdotes. The pharaohs, Solomon, Aristotle, Kings and Queens, Phoenicians and Venetians are a small part of this history, but here are two of the anecdotes:

"On her 121st birthday, Jeanne Calment of Arles, France, had a simple answer when asked how she survived to be the world's oldest-living person: olive oil. It appears in nearly every meal she eats and each day she rubs in into her skin. 'I have only one wrinkle,' she said, 'and I am sitting on it."

"Olives appear in unlikely places. One friend, half Greek, told me about Soula. In prewar Athens, fathers gave their pubescent sons a handful of drachma, a condom, and the address of a good-hearted prostitute. My friend's father went to see Soula. Having no diaphragm, she relied on an alternative protection from pregnancy: a fat Kalamata olive."

Here is chapter 1.

The heel of Italy's boot, Puglia, is currently in real trouble, olivewise.

The Farmer Trying to Save Italy’s Ancient Olive Trees. "A fast-spreading bacteria could cause an olive-oil apocalypse." One-third (2021)

of Puglia's 60 million olive trees have so far

been infected.

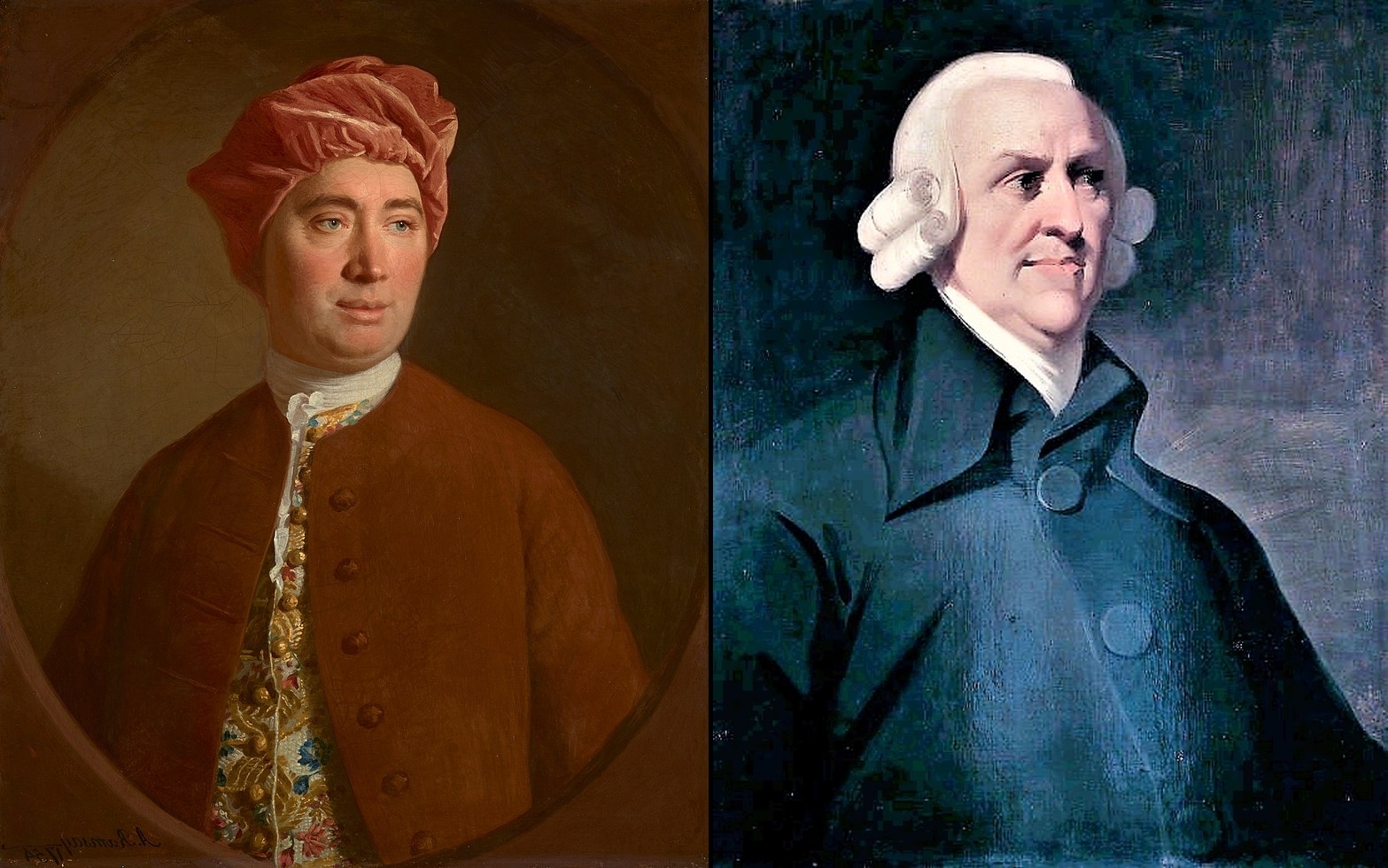

Two of the Scots who invented the modern world.

Hume

and

Smith -- click on name for xtra

How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything

in It. by Arthur Herman (2002)

Before going on to the grander claim, let’s take the assertion that Scotland was Europe’s poorest nation when this all began. The proof here is not a dull statistical comparison of all the

facets of the economies of each nation in Europe in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Rather it is a look at the history of Scotland in this period and the results it had in creating widespread

poverty. Violence and bloodshed planted their feet over and over in this period due to religious conflict (Presbyterians led by John Knox overturned Catholic influence) and disputes

about who should rule. A further contribution to poverty was a series of failed harvests, three of them, in the final years of the 1600s. Actually, Herman starts his book in 1697 with what he

considers a turning point, the hanging -- for Blasphemy -- of Thomas Aikenhead, a youth of about nineteen. This was the last of such hangings. Part of the indictment was that while a student at Edinburgh University he had

maintained “That the Holy Scriptures were stuffed with such madness, nonsense, and contradictions, that he admired the stupidity of the world in being so long deluded by them”. For

Herman, Aikenhead’s execution was “the last hurrah of Scotland’s Calvinistic ayatollahs.” It was the act of an old order. “Yet in 1696 this old order was already on its last legs.”

In fact, within the Presbyterian church system there were remarkable democratic elements, particularly in governance of the church itself. A 16th century contemporary of Calvin and

Knox, George Buchanan, wrote that God had invested power in the people, and they had the right to overthrow governments they found lacking. Scots were first to challenge King Charles I, something which eventually led to Charles losing his head in 1649.

Though beset with bloody turmoil and harvest failures, Scotland managed to pursue one great virtue -- its commitment to education. In 1696, it passed the Education Act (aka The Act for Settling of Schools) that ordered locally funded, Church-supervised schools to be established in every parish. Within any parish without a school and paid schoolmaster.

“a school will be founded and a schoolmaster appointed with the advice of the heritors and the parish minister.

to this end, the heritors of every congregation will meet, and provide

-- a suitable house for the school.

-- an annual salary for the schoolmaster, between 100-200 merks.

-- a new tax on heritors and life-renters to pay for these.”

Actually, Scotland had passed basically this same legislation almost 50 years earlier, but this new effort meant that “Scotland’s literacy rate would be higher than that of any other

country by the end of the eighteenth century" (75% in 1750). Publishers printed books, people read them, towns had lending libraries.

Scots valued not only education, but progress. Societies, like individuals, grow and improve, acquiring new skills, attitudes and understandings of what they can and should do. Those who executed Tom Aikenhead, however, were unaware of this, but history was leaving them behind.

The event which put all of this in high gear was the Act of Union in 1707, the passage of which is a story that Herman tells well. Scotland’s political autonomy vanished, but the union with England enabled them to benefit from England’s economy and international influence. The American colonies, for example, were now open to them, including the lucrative trade in tobacco, which Scots quickly exploited.

The Scottish Enlightenment followed. Francis Hutcheson, its Founding Father, at the University at Glasgow argued that people are fundamentally good, and they are motivated by their pursuit of happiness. Herman calls him “Europe’s first Liberal in the classic sense.” He had enormous influence, as did the lesser known Lord Kames, at the University of Edinburgh, mentor to David Hume and Adam Smith, a man who’s ideas inspired Gibbon’s classic work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Not all went smoothly, as with the Highland Clan’s last battle -- the defeat at Culloden in 1745. Back to Smith and Hume: the former, with his The Wealth of Nations, laid the foundation for modern understanding of economics, the latter dominated philosophy. Of Hume, he tells a wonderfully funny story. Taking a shortcut one day, Hume fell into a bog and started calling for help. An old fishwife heard him, but when she looked down and saw him, she realized this was “David Hume, the Atheist.” Hume pleaded that her religion must teach her to do good, even to her enemies. Maybe so, she said, but you’re not getting out until you become a Christian and repeat the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostolic Creed. Which Hume proceeded to do. She pulled him out.

(Herman does not mention this, but it is worth pointing out that this story is one where a fishwife recognizes a philosopher. That says something about education in Scotland,

does it not?)

James Watt did not invent the steam engine, but he made it actually work. He produced them with his partner Mathew Boulton. When James Boswell came to visit, Boulton said, “I sell

here, sir, what all the world desires to have: power.” Many of Scotland’s early industrialists had been trained in medicine. Edinburgh led the way, became the world’s #1 med school,

under William Cullen, had a great influence on science in general (encouraging experimentation). Prof. of Medicine and Chemistry was Joseph Black, physicist and chemist, known for his

discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. Anatomy was emphasized. At Cambridge and Oxford (where you had to be Anglican), med students were told

not to touch the patient. Not so Edinburgh, where it was “Hands On”. Edinburgh graduates Richard Bright, Thomas Addison, and Thomas Hodgkin all had diseases they discovered named

after them. When Darwin graduated from Cambridge and thought he wanted to be a physician, he went to Edinburgh (though he found the anatomy lectures dull).

Samuel Morse, of Code fame, was a Scot, as was Alexander Graham Bell. Steel magnate and tycoon, Andrew Carnegie, world’s wealthiest, was a Scot, as was James Clerk Maxwell,

mathematician who propounded a theory of electromagnetic radiation, describing electricity, magnetism and light as different manifestations of the same phenomenon -- called the

"second great unification in physics,” after Newton.

In politics, Scots had immense influence, especially in America, Canada and Australia. Andrew Jackson, James Polk, Rutherford B. Hayes. Patrick Henry, James Calhoun, Daniel Boone, Jim Bowie, Winfield Scott, William Clark -- all Scottish, as was the backbone of the revolutionary army. Princeton was founded by Scots Presbyterians and produced James Madison and Aaron Burr. David Hume said to Ben Franklin, “I am an American in my principles . . . and wish we would let (them) alone to govern or misgovern themselves as they think proper”

Eight of the ten founding fathers of Canada, were Scots, including the first Prime Minister, John A. Macdonald. Hudson Bay Company was Scottish. Herman tells Australia’s story at some length -- Australia, where landed Captain Cook, who was, of course, a Scot. Benjamin Disraeli claimed that he could go nowhere in the British Empire without finding a Scot and that Scot being in the lead in that region.

There’s much more in this book.

One review of Herman, says for balance we need to bring in some “harsher realities.”* “Given the traditional role of Highlanders as mercenaries and soldiers, some cultures' first contact with Scottishness is more likely to have been on the receiving end of a broadsword, bullet, whip, stick, knife, boot or fist. Scotsmen Matheson and Jardine are described as "the only two men who saw the potential of the opium market in China and had the skill and enthusiasm to do anything about it. If we substitute 'heroin', 'cocaine' or 'crack' for 'opium, and 'Afghanistan', 'Colombia' or even 'the UK' for 'China', then this vaunted duo are either nefarious drug barons or our current drug laws are still in the early 19th century."

* One of the "harsher realities" is the Ku Klux Klan: "which was formed by defeated Scots Confederate officers in the south. The 'order of the horse' oath ceremony recited by

Klan members came straight from Highland custom, as did that ancient Scottish symbol, the burning cross."

Note: Herman's book was published in the UK under the lame title: Scottish Enlightenment: The Scots' Invention of the Modern World

° STILL MORE

The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy

by Judith L. Pearson (2005, 2008)

Born and raised on a beautiful 110-acre farm in western Maryland, Virginia Hall was an outdoors girl from an early age. Her father taught her how to ride a horse, how to catch and clean fish, and how to use a rifle to hunt game birds and small mammals, something she did with enthusiasm and skill. At 5' 7" she was taller than most of the other girls at school, and she "was slender and pretty, with high cheekbones and a determined chin highlighting her face."

She started at Radcliffe, then Barnard, studying French, Italian, and German, but she wanted to finish her studies in Europe, and studied in France, Germany, and Austria. Her interest

was in the Foreign Service, and the best she could do, as a young woman, was an appointment to the Consular Service as a clerk at the American Embassy in Warsaw, in 1931. After a

few months, she transferred to Smyrna, Turkey, where an event in December 1933 changed her life.

The snipe is small, odd-looking, marvelous wading bird not often seen, though various species in the family range the whole world. Secretive by nature and about 10 inches long, weighing

only about 7 ounces, its brown and buff coloration helps its hiding in or near marshland. Eyes placed high on its head, it has a very long, slender bill which it uses to search for invertebrates in the mud with a "sewing-machine" motion. Hunters have difficulty finding them; they are highly alert and startle easily. In flight, hunters have difficulty wing-shooting due to the erratic flight pattern. In fact, the word sniper originally meant a hunter highly skilled enough to bring down this bird, only later acquiring the present meaning.

Virginia had hunted snipe in Maryland, but hunting them in Turkey would be a new experience, at a bog about 15 miles from the consulate, together with four co-workers. This was as much about camaraderie as about birds, and since snipe are most active during the late afternoon, the plan was to bring lunches and enjoy the outdoors before setting off to hunt. Her friends begged her to tell stories of her family; Virginia obliged with the tale of her grandfather, who at age nine stowed away on one of his father's clipper ships and ultimately became so successful at sea-going that he was able to buy his own ship and profit handsomely in the China trade.

All were in hunting clothes. Virginia was using her favorite, a twelve-gauge shotgun, originally her father’s. He had died unexpectedly two years before. Virginia was still telling stories when they came to a wire fence in bad condition. Three climbed over, and then it was her turn. She tucked her shotgun under her arm, leaving her hands free to deal with the slack top wire. As she lifted her right leg to climb, her left skidded slightly in the damp earth. The gun slipped, its trigger catching on a fold in her hunting coat. The gun went off and destroyed her left foot, “her blood staining the tawny field grass beneath where she lay.” None of her friends were trained in first-aid, but they knew that a tourniquet was needed, so tore at their clothing to fashion one. They created a stretcher out of their hunting coats and their unloaded guns and got her to the car.

Infection quickly set in, so much so that gangrene began to appear. The head doctor from the Istanbul American Hospital was rushed to Smyrna, and he determined that amputation below the knee was the only option. Red-hot burning pain and delirium followed (her father appeared before her and lifted her out of her bed and put her on his knee). Following her father’s advice to be a fighter, her recovery was amazingly rapid. By the end of February, she was able to return to the family estate in Maryland.

There was a delay there while her swelling abated and the skin that would adjoin the artificial leg toughened sufficiently to make using the prosthesis possible -- a hollowed out piece of wood with a hole into which she inserted her leg, covered by a sock for padding. A leather corset was affixed where wood and flesh join, one which laced up her thigh, containing also elastic straps that attached to a belt. It took several months to become proficient in using this apparatus, but by the fall she was seeking a return to work and on December 10, she was on her way to Venice.

Mussolini conquered Ethiopia by the end of 1936. In the following year, Virginia was renewing her attempts to pass the civil service examinations for entry into the Foreign Service. But of 1500 foreign service officials only six were women. In her case, an obscure provision disallowing amputees was invoked. In June 1938 she transferred to Estonia. In May 1939 she threw up her hands, resigned from the Consular Service, and moved to Paris.

When Hitler attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, Virginia was 33 years old. France and Britain declared war on Germany. Poland surrendered on the 27th. Russia had also declared war on Poland, on the 17th. Virginia’s new and very close friend, Claire de La Tour, told her that her brother was stationed on the impregnable Maginot Line. The two friends joined an ambulance corps and received basic medical training. They lived in a barracks, but not until spring did French-German skirmishes accelerate. Sent to live in a cottage near the Maginot, Virginia had to drive a vehicle which required her to use her artificial leg to depress the clutch. In May, Hitler invaded the Low Countries, both of which surrendered before the month was out, and his armies crossed the raging Meuse and penetrated the impenetrable Ardennes Forest, out flanking the Maginot.

Ambulance driving was hell. When not transporting wounded men, they slept where they could, ate almost nothing but bread and potatoes.

Startled by this, Virginia was even more startled when the medic found a photo in his boot. Virginia took the picture from the medic’s outstretched hand.

Laughing gaily at the camera was a handsome young man in uniform. Standing next to him, laughing just as gaily, blonde hair ruffled by a breeze, was Claire.The Woman Who Smashed Codes:

A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine Who Outwitted America's Enemies

by Jason Fagone (2017)

“He entered and stormed toward her, a huge man with blazing blue eyes. His clothes were more haggard than Elizebeth would have expected for a person

of his apparent wealth . . . he dwarfed her across every dimension . . . She had the impression of a windmill or a pyramid being tipped over her.” Fabyan’s first question to

Smith was, “Will you come to Riverbank and spend the night with me?” Such charisma. What girl could resist! She responded, “Oh, sir, I don’t have anything with me to spend the night

away from my room.” “That’s alright. We’ll furnish you anything you want.” He ushered her out of the Newberry Library, on Washington Square in Chicago, and then into his chauffeur-driven limousine.

Elizebeth Smith, from Huntington, IN, who wanted to be distinctive and who hated her “odious” last name, spelled her first name with an “e” because her mother wanted her 9th child, born in 1892, to never have to answer to “Eliza.” Elizebeth wanted to go to college, something of which her father disapproved -- but he later relented and loaned her some money, at four percent interest. Wooster College, in OH, for starters, though she completed her degree later at Hillsdale College in MI (Class of 1915). Poetry -- and philosophy, including Erasmus, who, she wrote, “believed in one aristocracy -- the aristocracy of intellect”. “He had one faith -- faith in the power of thought, in the supremacy of ideas.”

She was a remarkably insightful diarist. Round-cornered pages in that diary, on which she wrote with a quill pen about things like the importance of choosing the right words for things (she did not like the phrase “passed away”) and the importance of being honest.

In 1916 Elizebeth Smith left Huntington and moved to Chicago in search of a job. When she found that Newberry had one of very few copies in the world of the First Folio, the first printing of the works of Shakespeare, she went to see it. She told the librarian that she was looking for something “unusual, something in literature or research.” Elizabeth was 23, 5’3” tall, weighing not much over 100 lbs.

Enter George Fabyan, heavy-set, gruff, cigar-smoking Chicago businessman. Riverbank was George Fabyan’s creation, on the west bank of the Fox River in Geneva, IL. He founded it on his 240 acre estate there, in part to hire scientists, in part to prove that Francis Bacon wrote the works attributed to William Shakespeare. It was all there in First Folio, tiny clues that once detected, mounted up and mounted up and proved it really was Bacon. Fabyan assigned Elizebeth to the Bacon project under the supervision of Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who ran the Riverbank Cipher School.

Everyone lived at Riverbank. Rooms were provided. Meals were taken in common. Elizebeth met William Friedman, four years her senior, from a Jewish family in Pittsburgh who had gone to Cornell, was one of the scientists (had an interest in genetics), parted his hair in the middle. They toured Riverbank on bicycles together. He loved her.

The two came to doubt the Bacon project, the project which provided Elizebeth’s bread and butter. For one thing, the claim was that Bacon had written not just the works of the Bard, but of Marlowe and Ben Jonson, and others. For another, the hidden messages Gallup was finding, apart from “his” works of literature, were simplistic and inelegant, hardly the work of a great author.

[An aside: Norman Lewis, one of the great writers of the 20th (see Naples 44), a Welshman, had parents who became spiritualists. As a young man, Norman doubted. When his

father, a failed chemist, was channeling messages people wanted from deceased relatives, he found that even though the departed had been distinguished intellectuals, the message

they conveyed was never more profound than something like, “It’s lovely here.”]

2 WW2 Movies

Sahara (1943, Bogart)

If you drive through the parched Sonoran landscape between Palm Springs and Phoenix, passing trucks filled with seafood bound for scorching Las Vegas, at desolate

Chiriaco Summit you encounter the General Patton Museum. Why here? In the middle of nowhere?

It turns out that this is where Camp Young was located, and Camp Young was the training area for that Campaign in North Africa which began Patton’s fame.

The Brits captured Tobruk from the Italians in January 41, and Axis forces now led by Rommel took it back in June 42. Brits recaptured it on November 11 as part of their victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein. That same day Vichy French Forces surrendered to Patton’s 33,000 soldiers who had landed at Casablanca three days before.

Now, before Casablanca and much further to the east, as part of the Tunisian campaign, Bogart is not a nightclub owner but the commander of a primitive M3 tank, the Lulubelle, and two other guys,

Doyle and Waco. Attached to the British Eighth Army, "to get experience in desert warfare in actual battle conditions," they are now on their own in the Libyan desert, ordered to retreat south, their radio tells them, after Rommel’s taking of Tobruk. They soon encounter a bombed-out field hospital and pick up four Commonwealth soldiers (one played by Lloyd Bridges) and a Free French corporal, all of whom ride on top.

A bit further they see two soldiers in the distance, struggling up a sand dune. These turn out to be an Italian soldier and the Sudanese officer who has captured him. (Both played by remarkable actors, the latter by

Rex Ingram, of Cairo, IL, the former by J. Carrol Naish). Bogart agrees to take the Sudanese, but tells the Italian he ain’t taking no load of spaghetti, even if this is the middle of a sandy nowhere. And off the tank goes. Of course, he eventually turns the tank around.

They are strafed by a lone Luftwaffe pilot, but the tank manages to shoot the plane down. Bogart orders the Sudanese to search the pilot, who declares something in German. One of the Brits translates: “I would rather not be searched by a member of an inferior race.” Rather than leaving this prisoner to die, however, Bogart adds bratwurst to the spaghetti atop the tank.

The Sudanese knows where there is a well at an abandoned fortification, but after the long journey there, they find the well is dry -- except, one of the soldiers who descends to the depths discovers, for a steady dripping under one rock. Bogart sends Waco off to try to find British troops.

German scouts arrive in a half-track, in advance of a mechanized battalion, the commander of which rejects Bogart’s offer of water for food. A series of attacks are held off. The pilot gets a lecture from the Italian about what the Nazis are doing to his country, but the pilot then kills him and escapes, intending to reveal the truth about water. But the Sudanese runs him down and kills him. Eventually, however, there is only Bogart and one other left.

The final assault begins. But it turns out to be a surrender, as the battalion is literally dying of thirst.

There’s a surprise ending.

The film was made in February and March of 43 (in the California sand dunes near the Salton Sea). Primitive, but worth watching. Also, in the spirit of the then new US-USSR alliance, it copies ideas from a 1937 Soviet film which is available on YouTube:

The Thirteen.

[Update: US-USSR alliance now kaput].

Sahara itself is not available on YouTube (except in a weird, cropped version), but it can be seen here:

military-stuff.org.

Black Book (2006, Dutch)

Nearly seven decades later comes Paul Verhoeven to make a film about the Netherlands in the war, centered on the Dutch Resistance. Three times more expensive than any other Dutch film; voted best ever.

Warning: Watching Black Book is a lot more like an intense emotional experience than viewing a flic.

It begins in Israel in 1956, where Rachel Stein is accidentally discovered teaching elementary school by a friend of hers from the war years who is on a Holy Lands Tour. Bus and friend depart. Rachel begins to think about the war.

1944, and she is hiding with a Dutch family on a farm. Sunning herself by the lake, she is about to step on board a sailboat with a young man anxious to take this babe for a spin, when they watch a bomber come over head and destroy the farmhouse and the family.

Her boat friend drives her to a garage, where a man named Van Gein finds them that night. He says he came looking for them because he is a member of the Resistance and wants to help them escape. Soon, she’s reunited with her family and with about a dozen others boards a small boat at night, but it is ambushed by Nazi soldiers who machine gun everyone. Except Rachel, who dives deep into the water. The soldiers strip the bodies of valuables while Rachel watches from the water, hidden in the vegetation along the shore.

She joins the Resistance, a unit headed by Gerben Kuipers and working closely with a doctor, Hans Akkermans. She agrees to seduce Muntze, the local commander of the intelligence unit of the SS. She manages this with the help of his interest in -- postage stamps! A talented singer, at an SS party she finds herself on stage while the disgusting hulk, Franken, the officer who oversaw the ambush, accompanies her on the piano.

Working as a secretary at HQ, she falls in love with Muntze, whose family was destroyed when Berlin was bombed, He eventually realizes she is a Jew, but does not care, as he is love also.

She manages to plant a microphone in Franken’s office, which enables the Resistance to learn that Van Gein is a traitor. Akkermans plots to abduct Van Gein, despite the standing order that 40 civilians are to be killed in such an event. The plot goes wrong, and Van Gein ends up floating in a canal, shot repeatedly by Theo, a devout who had repeatedly said it was immoral to kill anyone.

Muntze countermands Franken’s order about the 40, and persuades his superior that Franken has been keeping all the valuables stolen from the Jews for himself. An inspection of Franken’s safe, however, comes up empty, and Franken accuses Muntze of negotiating with the Resistance, whereupon Muntze is arrested, imprisoned with captured Resistance fighters who are being tortured (one of whom is Kuiper’s son), and sentenced to death.

The Resistance comes up with a plan to free all from prison. Rachel agrees to participate only if Muntze also is freed. The plan is betrayed, the cells filled with soldiers firing machine guns. Rachel is arrested.

Ronnie, the Dutch woman who stumbled upon Rachel in Israel, and with whom Rachel has been working as a secretary, manages to help Rachel and Muntze escape.

Here things get complicated. The Netherlands is liberated by the Allies. Franken flees with his loot on a fast boat, but is killed by Akkermans. Smaal, a distinguished lawyer, and member of the Resistance, who

had helped Rachel’s parents and other Jews, is now suspected of treachery, and Rachel and Muntze confront him. He says the identity of the traitor can be deduced from his “Black Book”

in which he has recorded all his dealings with Jews. He is on his way to Canadian authorities, but as he goes out his office door, he and his wife are shot and killed by an unknown

assailant, who flees into the rejoicing crowds, Muntze racing after him. But Muntze is recognized and arrested by soldiers from the liberating army. Rachel is also arrested, as a collaborator, but

she manages to grab the Black Book. Muntze is brought before a young Canadian general, next to whom is standing Muntze’s superior officer, who is insisting that international law

requires that defeated armies be allowed to execute those they have sentenced to death within their own ranks. The young Canadian concedes, and Muntze dies in front of a firing squad.

Rachel is imprisoned with collaborators, humiliated in front of the others, and even tortured by the fervent anti-Nazi jailers. She is saved by Allied troops. Akkermans, now a colonel in the Dutch army, brings her to

his medical office, where, after he shows her loot he took from Franken after killing him, and telling her that Muntze is dead, attempts to kill Rachel with an overdose of insulin. But

she gobbles down chocolate the liberating troops have handed out. Akkermans walks out to the balcony to accept the cheers of the adoring crowd. Rachel soon appears beside him and

jumps down into the crowd. Akkermans pursues, but the crowd hoists him to their shoulders and marches in the other direction. Rachel proves her innocence to Kuipers, and Akkermans’

treachery, by means of the Black Book. She and Kuipers then intercept the fleeing Akkermans, who is hiding in a coffin in a hearse (a coffin Rachel had previously used to penetrate Nazi

defenses). The coffin has secret air vents underneath the wooden cross which is part of the cover, vents they screw down after killing the driver. They wonder what now to do with the money

and jewels. The scene shifts back to Israel, where we see Rachel and her new family walking back into a kibbutz which the sign says was funded with recovered money from Jews killed

during the war. Explosions are heard in the distance and a siren announces an air attack. Israeli soldiers take up their positions.

From The Glen Bard Book & Movie

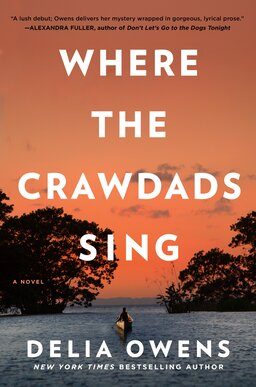

Book Review

Maariya Quadri, Editor

Protagonist: 4/5

Kya is an independent, hardworking, resourceful main character living off the land in the marsh. She’s the type of protagonist that you can’t help

but root for her til the very end.

Plot: 4.5/5

This book is quite multifaceted: while it is a tale of survival and love, it is also a murder mystery, and a brilliant one at that.

Setting: 3/5

The beautiful marshland setting is incredibly easy to imagine for readers, so much so that you’ll feel like you’re exploring the marsh with Kya.

However, the community of the nearby town is so cold to her that they tone down the pleasant nature of the book considerably.

Diversity: 2/5

The characters in Where the Crawdads Sing are mostly Caucasian, except for two Black American characters that provide Kya with the supplies and

support she needs to survive in the marsh.

Engagement: 4/5

While this story can be a bit description-heavy at times, you won’t be able to put it down. It’s an absorbing experience unlike anything you’ve

read, so much so that it truly doesn’t fit into any exact genre.

Film Review

Amy Tran, Editor

Cast: 3.5/5

The performances from the cast of Where The Crawdads Sing was exceptional. The way each and every actor/actress portrays their character evokes a

great amount of emotion from the audience whether that be proudness, pity, anger, or anxiousness. Similar to the book, there wasn’t much diversity

besides Mabel and Jumpin’ however their roles in the story were very significant.

Plot: 3.5/5

The plot of the movie stays relatively true to the plot of the book. It jumps between two timelines: One of Kya growing up in the marsh and learning

how to survive on her own and the other of the murder investigation and court case where Kya is the main suspect. From the very beginning of the movie, we get introduced to the court case almost immediately which takes time away from Kya’s childhood. If you’ve read the book, her childhood is explored so much and it really makes up who Kya is as a person. I wish we got to see more of that in the movie as it would have created a stronger emotional connection to her.

Cinematography: 4.5/5

Filmed in the State Parks of Mandeville and Madisonville, Louisiana, the cinematography of Where The Crawdads Sing is by far the best part of the

movie. The stunning wide shots of the marsh and its wildlife combined with its warm color tones allow the audience to see the marsh as Kya does—as

home.

Music: 3/5

Mychael Danna’s Where the Crawdads Sing OST (Original SoundTrack) blends non-western traditions with orchestral music to bring the marsh to life.

His pieces capture the wild marshlands of the North Carolina setting as well as the underlying mystery of the murder court case. Also in the album

is an original song by Taylor Swift called “Carolina,” a folksy song that is perfect for Kya’s story.

Engagement: 2/5

As much as I loved the film and everything that went into it, I didn’t find it very engaging. It may be because I already know the story and have

read the book, but never once during the movie was there a moment I felt on the edge of my seat despite the fact that murder mystery is one of its

main genres.

American Nations: a history of the eleven rival regional cultures of North America by Colin Woodard (2011)

Glenbardians think of themselves as living in the center of something called "the Midwest," the Heartland -- or even Chicagoland, as the Trib's founder, Colonel McCormick, used to describe

everything between the western border of PA and the Rockies. But not really, says Woodard, and in fact Midwesterners are really part of a culture called Yankeedom which stretches

from Boston through New England and NY (but not NYC), then skims the bottoms of Lakes Erie and Ontario, then engulfs MI, WI, MN and Northern IL. These are Puritans (who

were not Pilgrims) with not only a history of democracy made in town halls and respect for education, but an early and bloody intolerance, including the

Mystic Massacre in the war against the Pequot indians. Puritans also didn't like

Quakers, disfiguring them to keep track of them. They also obtained a royal charter by deception.

Wrapping around all this, one could almost say snaking around all this, is The Midlands which proceeds from Quaker Philadelphia west through central OH and IN, on into IA and eastern NE (with a southwesterly prong into eastern KS, western OK and even the very tip of the TX

panhandle) and then straight north up into Canada and back east over the top of Yankeedom all the way to New France. Midlands seeks a form of the Quaker's "inner light"

(Quakers gather in meetings not for voting but so individuals can find this light) and is pluralistic and averse to government intrusion. Greater Appalachia proceeds from WV alll through

central and southern OH, IN, IL, MO, AR, eastern OK and Northern TX. These are Irish, English and Scottish settlers who fled wars in their homelands, want ndividual liberty,

and are "intensely suspicious of lowland aristocrats and Yankee social engineers."

The US is not a united country, but a federation of eleven rivals. Other nations include El Norte (northern MX and our SW), The Left Coast, (a thin strip) The Far West (NE, all the way to the Sierra Nevadas), Tidewater, Deep South, New France,

and First Nation (far northern Canada and Greenland). New Netherland is NYC , Woodard has incredibly interesting things to say about each nation.

One of the main themes of the book is to overthrow a basic idea we were all taught in high school, that European settlement proceeded east to west as courageous settlers hacked out

living space in the wilderness, ever onward. "The truth of the matter is that European culture first arrived from the south, borne by the soldiers and missionaries of Spain's

expanding New World Empire." The English who stepped off the boat to found Jamestown in 1607 had been preceded not just by a few years but by a century. Spanish explorers

had "trekked through the plains of Kansas, beheld the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, and stood at the rim of the Grand Canyon" -- and mapped the coast of OR and BC, to say

nothing of their exploits in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1565 they founded St. Augustine, our oldest.

Another main theme, and the greatest part of the book's fascination, is how different the histories of each of these nations is, and how these differences persist to the present day.

Champlain's people dined and drank with indians and intermarried, a tolerance which

persists in our northern neighbor but which was shunned by our nations here; indeed, those Jamestowners refused to try unfamiliar foods, instead ate their dead, and still starved.

Charleston, SC, where the Deep South began, was founded by Brits from the Barbados, oldest and richest (but overpopulated) New World colony, one entirely built on sugar plantation

slavery. Tidewater slavery, which included such masters as Jefferson and Washington, was enlightened by comparison. Indeed, on the Chesapeake many blacks whose ancestors

had come to the region prior to 1670 had grown up in freedom, owned land, kept servants, even held office and took white husbands or wives. Women voted in NJ (briefly). Our Bill

of Rights is based on articles the Dutch extracted from the British upon the latter's takeover of New Amsterdam. Vermont seceded from NY (and tried to from US). Midlands Germans

were students of soil and forest conservation, as in Germany. Davy Crockett opposed the Indian Removal Bill. "Holy Fairs" began as early as 1801, way before Billy Graham (who

died 2/2018, age 99; Wheaton College grad). We might have taken over all of MX, but John C. Calhoun didn't like mestizos. Jefferson Davis could have negotiated Secession, but instead chose to

attack Fort Sumter, which changed everything. Henry Ford once put on a "Melting Pot" graduation ceremony/stage show in which people melted into a pot -- and then emerged as "Americans".

On and on stuff like this comes in this fascinating book. Who knew that Warren Harding founded OMB, the GAO, and the VA because he wanted government to work better? Or

that Quebec stays in Canada because the northern 2/3 of the province is Native American and isn't going anywhere. The leadership of Greenland is female.

Politically, El Norte grows in importance.

** actually, Chicago was originally part of Yankeedom (Marshall field was from Conway, MA), but became multi-ethnic -- Yanks moved to Evanston.